We all know the rules of safe highway driving: no talking on mobiles, no zipping between lanes and no putting your arm around your honey as you motor along.

That last one could earn you a $10 fine and 10 days in jail back in June 1940, as one fellow found out after being pulled over on the Toronto-Hamilton Highway, known today as Lakeshore Road. “The car was weaving on the road,” the arresting officer told the magistrate. “And [it] was travelling at 55 miles an hour.”

That same month, a similar charge for careless driving on the Queen Elizabeth Way was dismissed after the accused denied having his arm around his wife, an account his wife corroborated in court.

Cars, trucks and buses. If you live in Mississauga, odds are you spend a significant portion of your time in some form of motorized transportation, which means you’ve likely spent some time travelling on two of the city’s original east-west motorways: Lakeshore Road and the Queen Elizabeth Way.

In 1906, there were 1,000 motor cars in Ontario, but by the early teens, motor cars could be frequently seen bouncing along gravel and dirt roads designed for horses and buggies, both in terms of comfort and maximum speed. Congestion was a common problem, particularly as motorists sought to venture out into the countryside on longer trips.

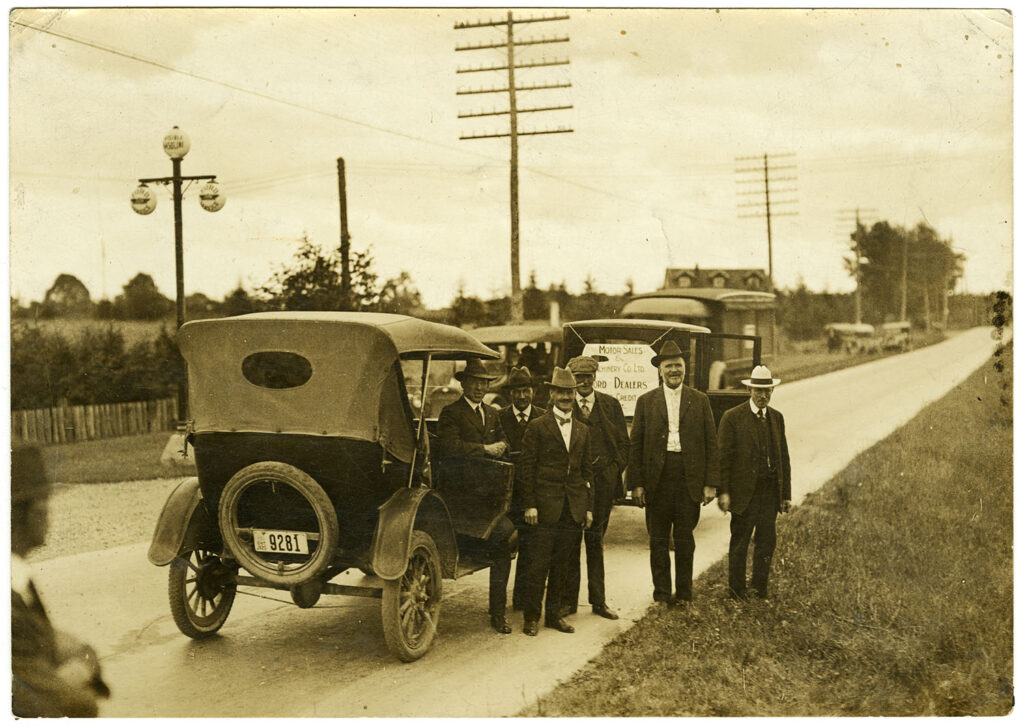

George W. Gordon (far right) of Port Credit was a farmer, justice of the peace and magistrate, making him an early enforcer of Ontario’s driving regulations on the new Toronto-Hamilton Highway. He is standing next to his good friend and fellow justice of the peace Reuben Lush, namesake of Clarkson’s Lushes Avenue, and member of the Toronto and Hamilton Highway Commission, circa 1916. (Photo credit/Port Credit Library Collection)

A roadside fruit and vegetable stand that claimed to be the first in Ontario on the the Toronto-Hamilton Highway, sometime between 1914-1917. (Photo credit/Region of Peel Archives)

To solve the problem, engineers and planners turned their attention to the former Indigenous pathways, now Colonial-era concessions roads that hugged the shore of Lake Ontario. While well-travelled in the 1800s, by the turn of the last century, the roads had been usurped by railways as the primary form of transportation between Toronto and the adjacent rural towns, villages, and townships.

For instance, by 1905 the Toronto and Mimico Electric Railway and Light Company operated the Lake Shore line from Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood through Mimico, Long Branch and ending in Port Credit – a forerunner to today’s GoTrain line.

But with the arrival of motor cars, engineers and planners decided to build a paved highway atop the old Colonial and Indigenous roads.

In 1914 the route between Hamilton and Toronto opened, passing through Clarkson, Port Credit, Long Branch and Lakeview in present-day Mississauga.

The Toronto and Hamilton Highway, now known as the Lakeshore, under construction, the first paved road in Ontario. This photo was taken between 1914 and 1917. (Photo credit/Port Credit Library Collection)

The project had two lasting effects. First, it converted the Lakeshore Road, which at the time was made of crushed stone, into Ontario’s first paved intercity highway. Second, a new government department was created in 1917 to oversee the expansion of the new highway between Pickering and Port Hope; the Department of Public Highways.

By 1920, the Department had taken ownership of a series of roads connecting Windsor with Rivière-Beaudette on the Quebec/Ontario border. In 1925, the provincial roadway was renamed Highway 2, the first numbered highway in Ontario. It would eventually connect with similarly numbered highways in Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, traversing eastern Canada from Windsor, ON to Halifax, NS.

Highway 2 remained Canada’s primary east-west thoroughfare until the opening of Highway 401 in 1968.

This paved highway heralded the arrival of another aspect of modern life: traffic congestion.

By 1925, there were 200,000 motorized vehicles in Ontario, all of which were causing stop-and-go traffic on Highway 2/Lakeshore Road.

In response, the provincial government announced a new road, twice as wide as Highway 2, that would be built between Toronto and Burlington, beginning with the expansion of the Middle Road, so named because it was located south of Dundas and north of Lakeshore, traversing Toronto Township and Oakville.

Then, in 1934, Robert Smith, the deputy minister of highways, upgraded the plans, ordering the building of a dual-lane divided highway, following the lead of Italy (autostrata), Germany (autobahn) and New York State (state parkways).

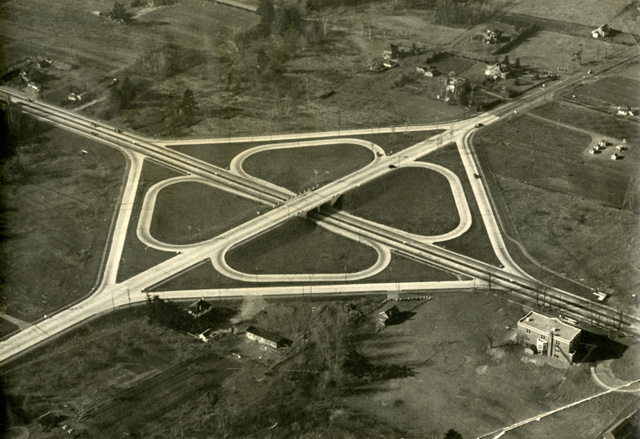

Initially known as the Middle Road Highway when it opened in 1937, it was the first intercity divided highway in North America and boasted Canada’s first cloverleaf interchange at Hurontario Road.

An early photograph, circa 1940, of the first cloverleaf interchange in Canada at QEW and Hurontario. Built in 1937, the QEW originally ran beneath Hurontario. It wasn’t until 1962 when the current cloverleaf was built with the now familiar Hurontario underpass – upon which Mississauga’s LRT line will run. (Photo credit/Port Credit Library Collection)

Two years later, on June 7, 1939, Queen Elizabeth and her husband, King George VI, parents of the future Queen Elizabeth II (then a 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth), drove beneath a pillared gateway in St. Catharines, officially opening the highway and revealing its new name: Queen Elizabeth Way.

“[T]he Royal entered the still unpaved section of the highway at Niagara Street, near the city’s northern limits, thereby giving plenty of time for Their Majesties to see the unveiling,” wrote the Globe and Mail’s report. “The car did not slacken speed but Their Majesties were seen to examine intently the arrangements.”

Among its other accomplishments, the QEW was the first fully illuminated highway in the world, with art deco-styled lamp posts – identifiable by the familiar swooping ‘ER’ logo for Elizabeth Regina, Latin for Queen Elizabeth.

The Queen Elizabeth Way crosses Etobicoke Creek in a photo from around 1957. Today, this section of highway includes a bustling interchange with Hwy. 427 and the Evans Avenue/Browns Line exit to Sherway Gardens and Etobicoke. (Photo credit/Port Credit Library Collection)

It was also the route many families followed in the 1950s to purchase homes with yards and carparks in suburban developments that included schools, shopping and parks.

While farms continued to flourish north of Dundas, in the 1950s, subdivisions such as Applewood Acres, Erindale Woodlands and Park Royal opened along Mississauga’s two original motorways – Lakeshore Road and the QEW.

A new city was on the move.