Next time you bite into your favourite sandwich or savour your favourite baked good, look down because the ground you’re walking on has been continuously feeding Canadians for over 200 years.

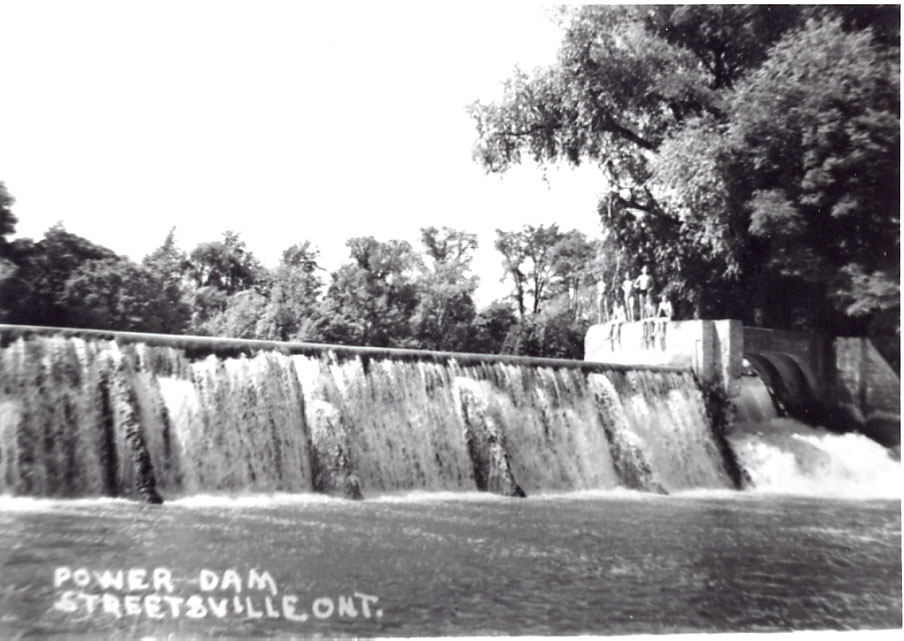

It’s all thanks to the Credit River, the waterway that defines and shapes life in Mississauga – and which literally made the area’s early wheels of industry turn.

Along its banks in the early 1800s, a series of grist mills were built, using early hydro (water) power to turn wheat into flour.

Grist mills produced flour by crushing grain between two millstones, one of which turned via the power of water flowing over the slats.

Streetsville owes its existence to these mills.

The land north of Dundas Street was fertile ground for wheat and grains, so that’s what early settlers planted.

Initially, settlers would have milled flour for themselves, but it wasn’t long before entrepreneurs stepped in to ramp up production and establish an export market to sell the milled flour to Great Britain.

In 1821, Timothy Street, for whom Streetsville is named, built a water-powered grist mill and sawmill, followed by a lumber mill on the banks of the Credit River, which, in addition to providing fresh water and fish, was a free and natural source of energy.

There was a buzz in the air around Streetsville, which attracted others, such as American immigrants Heman and Mary Hyde, who, in 1824, opened the first hotel on Queen Street. They called it Ontario House, but the locals just called it Mother Hyde’s.

In 1847, the Hydes sold the hotel and built a large grist mill at the foot of Ontario Street. Six storeys high and with four grindstones, it was the largest business in the area, and it soon included a stave factory, which created those familiar wood slats for barrels, and cooperage, which built the barrels for distilleries, wineries and shipping flour and other dry goods.

They called the entire complex Ontario Mills, which gave its name to modern-day Ontario Street in Streetsville.

In 1907, the old mill was converted into the region’s first municipally-owned hydroelectric plant, which produced power for the Town of Streetsville until 1975. Today, the one-storey stone and brick remnants of the Hydes’ Ontario Mills can be seen at the base of Ontario Street.

The area continues to feed the country via Ardent Mills, which operates on the site of the Beaty Mill, which started in 1837. While John Beatty may have purchased it, his widow Helen ‘Hetty’ Beatty turned it into a busy family-run business, which she led for close to 20 years.

Hetty Beatty was one of Mississauga’s earliest female business leaders and entrepreneurs.

The mill remained in the Beaty family until 1895 when Duncan Wallace Reid took it over and renamed it Credit Valley Flour Mills. Reid expanded the business and introduced state-of-the-art technology while continuing to mill its flour using water power alone.

After 130 years of operations, the Reid family converted to electricity in 1964.

The family sold the mill in 1969, but the name Reid Milling remained, and a third generation continued to manage it.

The Reid family formally transferred their remaining ownership to Nabisco in 1984, and Reid Milling became Nabisco Milling in 1998.

Kraft owned it in the early years of this century and sold it to Ardent Mills in 2015.

Today, Ardent Mills is the largest soft wheat flour mill in Canada and the second-largest in North America. It is capable of producing 400,000 kilograms of flour each day on the site of Hetty Beatty’s earlier mill.

Streetsville celebrates its milling story each spring at the Streetsville Founders’ Bread and Honey Festival. Initially created in 1973 as a farewell party for the Town of Streetsville as it prepared to amalgamate to form the City of Mississauga, the festival has grown into Mississauga’s largest and longest-running festival.