Some of Canada’s largest fortunes were wagered in the race to settle the west.

The men in suits began knocking on farmers’ doors in the 1950s, with offers few could refuse: enough money to retire in exchange for deeds to the farms that lay west of Toronto.

They had a single aim: to purchase thousands of acres of farmland, hold it and then, when the price was right, develop it for the expected population surge.

For instance, E.P. Taylor, one of Canada’s richest men, was the chief initial backer of Erin Mills.

Taylor was the founder and head of Argus Corporation, the holding company for a variety of well-known Canadian brands, including Dominion Stores, Domtar, Standard Broadcasting, Massey Ferguson, and Canadian Breweries Ltd.

Teaming up with Cooksville-raised, Harvard-educated urban planner Macklin Hancock, the pair set out to create a ‘new town’ of broad avenues, curving streets and spacious, modern homes far from the cramped quarters of downtown Toronto.

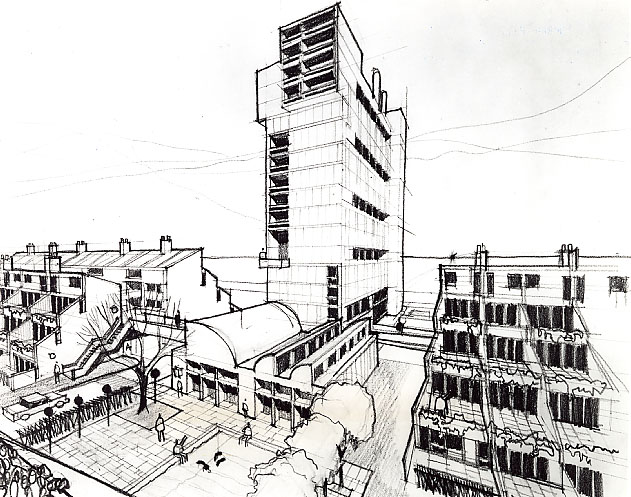

Photo of a conceptual drawing showing new kinds of apartment housing to be built in Meadowvale. (Photo credit: Mississauga Library).

To begin, the pair went north, creating Don Mills in 1953. Hancock’s vision wasn’t simply to build suburban housing; he intended to design a self-sufficient town. Don Mills was a mixed-use neighbourhood divided into four quadrants, each centred around a school, a park and a church. In the centre, Hancock placed all the shared community services: the community centre, hockey rink, library and shopping centre, all surrounded by a greenbelt.

Hancock and his design team put strong controls on all Don Mills developments. His sister Marjorie, who had recently graduated from the Ontario College of Art, now OCAD, set the colour palette for all buildings, regardless of its purpose. Churches, factories, private businesses, and national chains had to adhere to the Hancocks’ colour schemes.

Don Mills’ design was so popular before he was done Hancock was asked to design similar new towns, complete with cul-de-sacs, distinct colour palettes and connecting walking paths in the burgeoning Toronto Township.

Taylor and Hancock sought to replicate their success in Don Mills with a similar development north of the QEW near Erindale.

In 1955, the Erin Mills Development Corp. purchased 7,200 acres within the Credit River watershed, choosing the parcels based on topography rather than municipal boundaries. It stretched north from Dundas Street with the Credit River, its eastern boundary, and Trafalgar Township, later the City of Oakville, its western border.

Then they waited. The sticking point was money.

Photo showing an unidentified park and a bike and walking path with numerous bikers and pedestrians. In the background are single detached houses and their corresponding backyards. (Photo credit: Mississauga Library).

Toronto Township Council was concerned the speed of industrial development was not keeping pace with residential construction. This was a problem because a typical municipal tax structure required a mix of 60 percent residential and 40 percent industrial and commercial.

That balance had been upended in the 1950s with the rapid expansion of residential construction along the QEW between Etobicoke Creek and Hurontario, causing Toronto Township’s tax base to become a 70/30 split, with residential taxes accounting for the larger percentage.

According to Reeve Robert Speck, that made budgeting for municipal services, specifically education, a harder task.

When developers presented their plans to Toronto Township, the municipality insisted approval was conditional on the developers agreeing to pay the Township’s costs for education for students living in Erin Mills.

Factor in the additional financial investment required to expand water and sewage infrastructure in Clarkson and Streetsville and it quickly became apparent that Erin Mills would take longer than its predecessor.

Fast forward to 1969, and Erin Mills, now owned by Cadillac Development Corp., Canadian General Securities and the Bronfman family’s Cemp Investments Ltd., was once again before municipal officials.

This time, it was joined by its northern neighbour, Markborough Properties Limited.

Markborourgh had an equally expansive vision for its new town concept, Meadowvale, a 2,300-acre development at the intersection of Highway 401 and Mississauga Road, and the money to back it.

The publicly-traded investment company was a who’s who of Bay Street corporations: Holborough Investments Ltd., which was owned by Aluminum Co. Of Canada (ALCOA), the Bank of Nova Scotia and Greenshields Inc.; Air Canada Pension Trust Fund; Canadian National Railways Pension Trust Fund; Canada Life Assurance Co.; Canada Permanent Mortgage Corp.; Equitable Life Insurance Co.; L-Industrielle Compagnie d’Assurance sur la Vie; the Investors Group; the Mutual Life Assurance Co. Of Canada; North American Life Assurance Co.; contractor George Wimpey Canada Ltd.; British American Oil Co. Ltd., owner of the Clarkson refinery; and realtor A.E. LePage.

Erin Mills and Meadowvale were pitched as a $1.25 billion development that could accommodate up to 200,000 people, supported by an $88 million provincial government investment in a new sewer and water system, drawing water from Lake Ontario to carry it north to Streetsville.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, the twin developments came together in phases – new towns to populate a new city.

You can hear more stories about the people and events that helped shape Mississauga via our podcast, We Built This City: Tales of Mississauga, available on your favourite podcast platform or from our website.