During university, I spent my summers working at the Petro-Canada refinery in Clarkson. My base of operations was the maintenance department, a single-storey building located across from the asphalt plant and near the welding shop.

One day a couple of tradesmen walked in, their arms filled with lilacs. The smell of springtime filled the office, which considering our proximity to the asphalt plant, was no mean feat.

Where did all these flowers come from? I asked.

From ‘the old crescent’, long abandoned, located in the northeast corner of the property, just across the fence from the Bradley House Museum

I asked to see it and so one of my breaks, I found myself standing on an old semi-circle road, the asphalt cracked and covered in weeds, the only evidence that people had once lived here.

I walked up to one of the old front steps leading to a cement foundation amidst the overgrown lilac bushes and thought, huh, so this is where my family’s story in Mississauga begins.

British American Oil Company was neither British nor American; it was 100 per cent Canadian, founded in Toronto in 1907 by Canadian businessmen Albert Ellsworth and Silas Parsons.

BA’s first major expansion was to Montreal, and in the mid-1930s the company started to explore constructing a refinery in the farming community of Clarkson, on the shores of Lake Ontario.

But history intervened. In 1939 war was declared and two years later the government of William Lyon Mackenzie King came calling.

It needed the Clarkson refinery built ASAP, but not to produce gasoline. It needed airplane fuel.

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan was prepping pilots for the war effort at bases across the country, including at the newly-opened Malton Airport, 30 kilometres northeast of Clarkson.

More than 10,000 planes were required – and they all needed fuel.

The new BA Oil refinery in Clarkson opened to much fanfare on November 15, 1943. It was one of the world’s most modern refineries and the only refinery in North America that didn’t make gasoline. It exclusively made fuel and lubricants for planes.

BA also built housing. It had to in order to attract the skilled workers it needed to operate the refinery, which was located 35 kilometres west of downtown Toronto.

Marigold Village with its 50 homes built on a crescent was located about 50 yards south of where Clarkson Road South meets Orr Road.

BA Oil maintained Marigold Crescent from 1943 to 1964 for its employees and their families. My parents moved onto the Crescent in 1956 and stayed for the remaining eight years.

Local officials are on hand to mark the start of construction on a fuel gas scrubbing plant at British American’s Clarkson Refinery. From left: Toronto Township Ward 2 Councillor, R. K. Harrison; BA Oil Refinery Manager, W. E. Lundie; BA Oil Vice-President L. P. Blaser; and Toronto Township Reeve, R. W. Speck. (Photo courtesy Mississauga Library)

On maps it’s called Marigold Village but to my parents and everyone who lived there it was always just The Crescent.

My parents’ first home in Mississauga had been an apartment above a strip plaza in Port Credit. Rent was $80 a month.

My sister Kathy took her first steps there, but in spring 1956, with my mom expecting my sister Carolyn, my Dad went to BA’s HR department and asked to be considered for a house on Marigold Crescent.

They moved into a bungalow shortly after that. It had two bedrooms, a kitchen, a bathroom and a living room, and the Silverwood’s Dairy milkman dropped bottles of milk in the milk chute by the basement door.

Rent was $48 a month, almost half what my parents had been paying in Port Credit, and because the homes were owned by the refinery, my parents’ rent never increased. And they had no other fees. Electricity, property taxes and all maintenance costs were covered by BA.

The company employed a man fulltime to maintain the homes on Marigold Crescent. He painted the clapboard houses, fixed what was broken and restocked the coal chutes.

For my parents and the other young families, Marigold Crescent was a special place. Because all the men knew each other from work, and Marigold Crescent wasn’t part of a larger subdivision, the families formed a strong bond.

They had corn roasts and picnics. The stay-at-home moms would get together at each other’s homes for morning coffee visits, and walk to the end of the crescent each afternoon to meet the school bus as it dropped off their children.

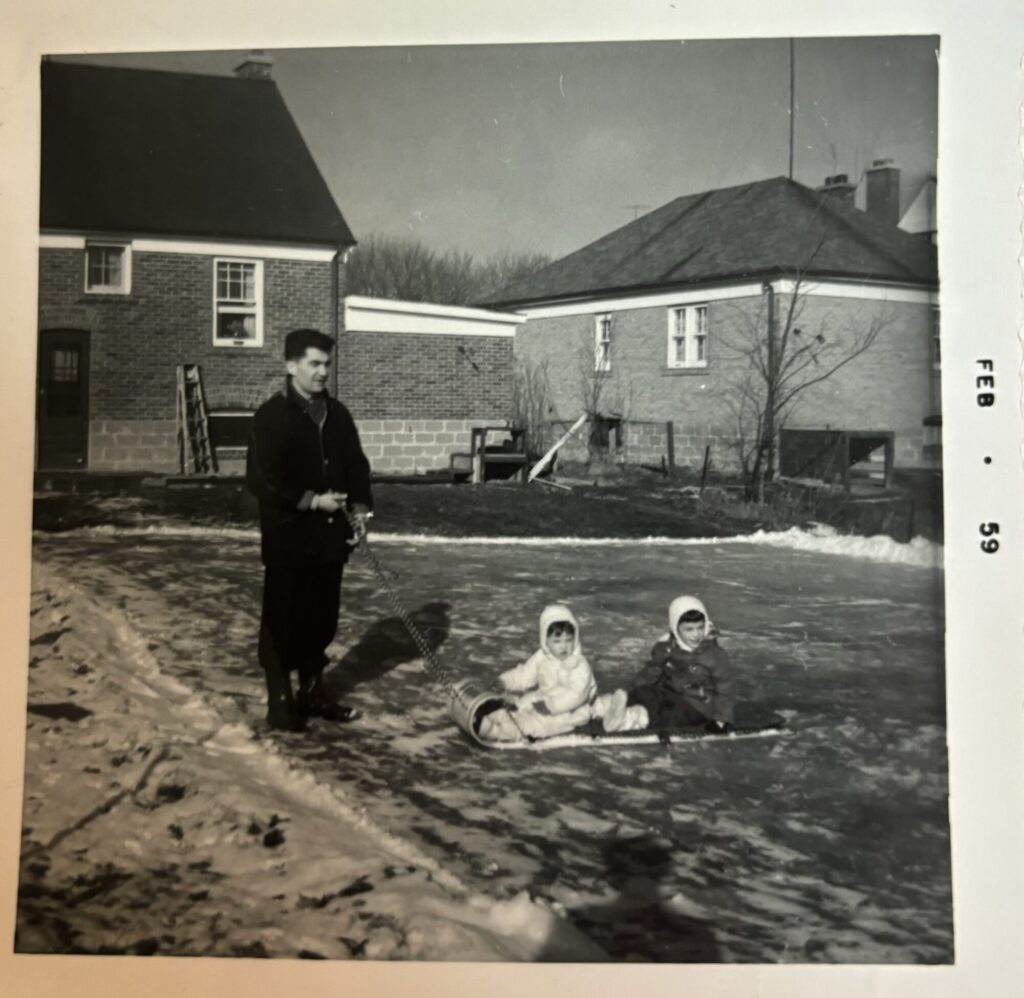

The company built a ballfield for baseball in the summer, and an ice rink in the winter. The kids would play on it until it was time for bed and then, at 10 pm the men, my dad included, would go out on it for games of shinny.

Afterwards they’d flood the rink, so it would freeze overnight and be ready for the kids the next day.

When BA Oil decided to shut down Marigold Crescent, they gave families a year’s notice.

Some, like my parents, moved into one of the new subdivisions popping up in Clarkson and Lorne Park.

A few families opted to relocate their physical house and today three of the original Marigold homes sit on Orr Road, while a fourth is located across the street from Canadian Tire on the east side of Southdown Road.

Reminders of how the story of suburbia began to take shape in the fields west of Toronto.

The author’s dad, Matt Hrabluk, pulls sisters Carolyn and Kathy on a toboggan in the backyard of the family’s home on Marigold Crescent in 1959. (Photo by Fran Hrabluk)

You can hear more stories about the people and events that helped shape Mississauga via our podcast, We Built This City: Tales of Mississauga, available on your favourite podcast platform or from our website.