When the door closed on A.V. Roe’s famed supersonic jet the Arrow, a window opened for a new company to take Canadians to space.

The AVRO Arrow is often regarded as a heartbreaking story of Canadian innovation undone, but while the jet may have been destroyed, the technology and the human expertise continued to flourish, creating Canada’s most famous aeronautic marvel: the Canadarm.

In 1962, following the cancellation of the AVRO Arrow program, A.V. Roe’s aircraft facility in Malton was transferred to de Havilland Canada, including the company’s Canadian Applied Research arm, which tested new ideas and innovations.

De Havilland’s Canadian engineers had a similar ‘special projects’ division, where they explored innovations in space technology, satellite communications, and advanced engineering.

As the global space race took off, engineers from these two innovation hubs combined under one name at de Havilland – special projects and advanced research, or SPAR for short.

This small group became increasingly involved in the burgeoning field of aerospace technology, which was outside the core business of de Havilland, known as a manufacturer of Canadian bush planes, such as the Otter and the Beaver.

So, in 1967, De Havilland sold SPAR to a group of current and former Canadian employees. The new company’s first president was Larry Clarke, De Havilland’s former vice-president of administration and planning.

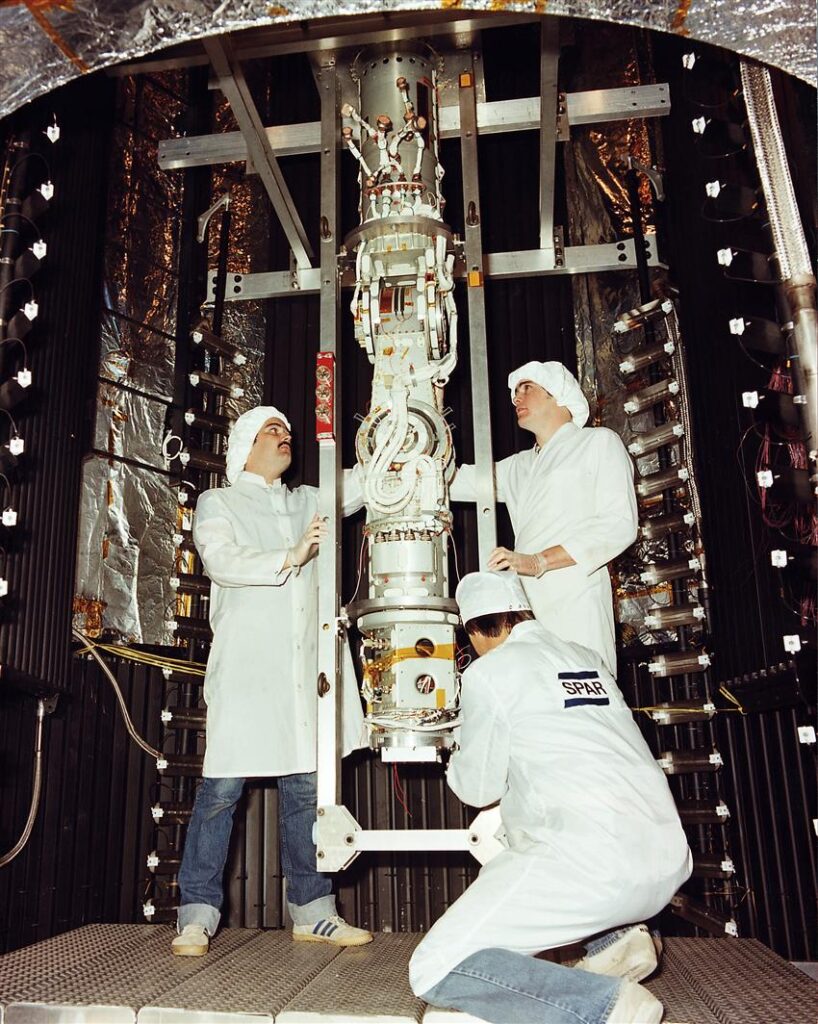

Canadarm, the robotic arm that would later be installed on the Space Shuttle, without its sleeve during testing. (Photo Credit: Communications Research Center Canada (CRC) Photo courtesy of the Canadian Space Agency)

A couple of days later, on January 3, a small ceremony was held at the SPAR plant on Dixon Road, just north of the airport in Malton. The new company had 460 employees, a contract to build the Isis-A satellite for NASA, and 700,000 shares with a starting value of $2/share.

The company quickly gained recognition for its expertise in space technology and robotics, developing numerous components for communications satellites and scientific instruments for space research.

In 1970 Telesat Canada contracted SPAR to build the spacecraft structures for Canada’s first domestic communications satellite and to provide up to 15 additional spacecraft for sales to international markets.

SPAR was also expanding through acquisitions of companies such as York Tools and building a $1-million modern plant on Caledonia Road in Toronto.

Then in 1974 NASA came calling. Two years earlier it had publicly unveiled its predecessor to the Apollo, Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz space programs; a ‘space truck’ that would shuttle people and supplies between Earth and the United States’ proposed low Earth orbit space station.

Canada wanted a piece of that giant leap forward in space exploration. To do that the National Research Council (NRC) brought together national leaders in aerospace technology to propose supplying NASA’s space shuttle program with a remote manipulator arm for handling space-bound payloads.

According to NASA the arm needed to be strong enough to hold heavy equipment while also capable of precise movements while transferring payloads in zero gravity.

The estimated cost: $35 million, the bulk for the development and manufacturing of the shuttle-attached manipulator system, SAMS for short. At the time, the manipulators were described as resembling extended grasshopper arms.

On May 6, 1975, NASA announced a team of Canadian companies would develop the manipulators, led by SPAR Aerospace, with delivery expected by early 1979, in time for the expected first launch of the U.S. space shuttle. Rounding out the team were Montreal-based companies CAE Electronics and RCA, and the federal government’s Communications Research Centre.

A key player in SPAR’s foray into space travel was vice-president of marketing and planning John McNaughton. A mechanical engineer by profession, the Mississauga-based McNaughton had a natural talent for marketing, and in particular selling government officials on big audacious ideas.

It was McNaughton who convinced both his colleagues at SPAR and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s government that the future of the nation’s economy lay in space.

In 1981 the world watched as the Canadarm — a marvel of engineering — gently unfurled into space. For Canadians watching, the Canadarm wasn’t just a piece of technology; it was a symbol, a marker of Canadian pride.

NASA astronaut Richard Truly deploys the Canadarm from Space Shuttle Columbia’s cargo bay for the first time on November 13, 1981. Occurring during Shuttle Mission STS-02, he described it as “work(ing) beautifully.” (Photo credit: NASA; Photo courtesy of the Canadian Space Agency)

We have MacNaughton to thank for showing us how to wave the maple leaf proudly in space. He pitched the Canadarm idea and name so effectively that the government thought it was their own.

Before long, every time the shuttle’s cameras broadcast the Canadarm at work, millions of viewers saw the red “Canada” logo, a testament to McNaughton’s branding genius.

Even in retirement, McNaughton filled his Mississauga home with the latest in technology. One of his final purchases before he died in 2006 was a GPS unit.

“He didn’t need it to navigate,” quoted the Globe and Mail of what his children had to say at his eulogy. “He cherished it because on its display he could watch the various satellites lock into his coordinates on Earth.”

For his pioneering role in Canada’s space industry, Mississauga resident John McNaughton was inducted as a member of the Order of Canada in 1997.

In 1999 SPAR’s Space and Advanced Robotics Division, which built the Canadarm and the Mobile Servicing System for the International Space Station, was acquired by MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates (MDA).

Its technology, innovations and human expertise continues to influence and advance satellite manufacturing, Earth observation and space exploration achievements from its global headquarters in Brampton, ON, home to Canadarm3.

You can hear more stories about the people and events that helped shape Mississauga via our podcast, We Built This City: Tales of Mississauga, available on your favourite podcast platform or from our website.