Imagine discovering that your family’s story is a lie that your parents told to keep you safe from a curious public – and dangerous foreign agents.

It’s the stuff of spy novels, except for the eight Krysac siblings, who each learned the truth when they turned 16: their parents’ real names were Svetlana (Anna) and Igor Gouzenko, and their father was once the most famous Soviet defector in the world.

Let’s set the scene. It’s Wednesday, September 5th,1945. The Second World War officially ended that weekend, and Canadians were celebrating.

That night, at around 9 p.m., a handsome young man of average height walks quickly down the street, casting nervous glances over his shoulder as he approaches the offices of the Ottawa Journal. He’s sweating; it’s a hot and humid night in the nation’s capital, but he’s nervous too.

His name is Igor Gouzenko, and for two years, he’s worked as a cipher clerk, relaying messages between agents in Canada and officials with the GRU, the Soviet military intelligence agency, the GRU, from its embassy on Charlotte Street.

But on this night, that’s about to change.

Agitated, he makes his way to the desk of the Journal’s night editor and, in heavily accented English, blurts out, “It’s war. It’s war. It’s Russia.”

The night editor looks at Gouzenko, confused. He can barely understand the man and eventually suggests Gouzenko visit the RCMP, which has an office in the Justice building close to the newspaper office.

Once at the Justice building, Gouzenko approaches the policeman on duty and asks to speak to the Minister of Justice, Louis St-Laurent. The policeman politely suggests the nervous man return during business hours the next day.

Which he did, this time with his pregnant wife Anna, and their two-year-old son Andrei in tow. The trio waited two hours before being turned away by St-Laurent, then they were rebuffed by the Journal’s daytime newsroom, and the RCMP refused their request for protection.

Finally, after leaving their exhausted and cranky toddler with a neighbour, the Gouzenkos found a willing official in Fernande Coulson, a secretary with the Canadian Crown Attorney, who promptly called John Leopold, the RCMP’s assistant chief of intelligence, who agreed to see Gouzenko the next day.

It was an odd start – more Slow Horses than James Bond – to what would become The Gouzenko Affair, a series of events and revelations that launched the Cold War in the public consciousness.

Gouzenko brought over 200 documents detailing an extensive Soviet spy network operating in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain, that led to 20 arrests in Canada.

He was interrogated by officials from the FBI and the British Secret Service, including Canadian William Stephenson, the real-life model for James Bond.

With fears of retaliation from the Soviets, the Gouzenkos went into permanent hiding, first in a series of summer cabins outside Ottawa, then at Camp X, the secret spy camp created by Stephenson outside Whitby.

In 1947, the family moved into a two-acre home at 2230 Mississauga Road, down the street from the Mississaugua Golf and Country Club.

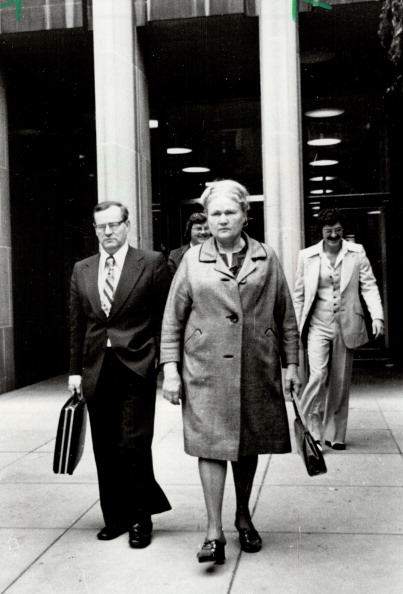

A rare photo or an unmasked Igor and Svetlana Gouzenko taken in 1975. (Photo by Bob Olsen/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Here they were known as Stanley and Anna Krysac, with a gaggle of kids who attended Lorne Park Public School, played hockey, joined the Brownies – and got accustomed to their parents’ hushed evening conversations in a language they didn’t understand.

Despite living under an assumed name, the Gouzenkos didn’t retreat from public life.

In January 1958, Anna made the front page of the Port Credit Weekly to thank the unknown young man who had jumped in to stop her car from rolling down the Lakeshore after she’d parked it to pop into the hardware store, leaving 12-year-old Evelyn and one-year-old Bobby inside.

“In a statement to The Weekly, Mrs. Krysac announced she and her husband intend to reward the young man if he contacts her at home.”

Igor, in particular, gravitated to the public spotlight, always appearing on television or in the newspaper with a white pillowcase over his head, with two cut out eyeholes, to shield his identity.

The pillowcase had been Anna’s idea; the kids were mortified once they figured out that it was their dad they were watching on the evening news.

Gouzenko wrote two books, his 1948 memoir This Was My Choice and the novel The Fall of a Titan, which won the Governor General’s Award for fiction in 1954. He and Anna were visual artists; he sold his paintings while Anna worked for a time in real estate.

The Gouzenkos story was also made into two films: The Iron Curtain (1948) starring Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney, and Operation Manhunt (1954).

Igor Gouzenko died of a heart attack on June 25th, 1982, and Svetlana on September 4th, 2001 – exactly 56 years after they made the fateful decision to escape to Canada.

They were buried in unmarked graves in Clarkson’s Spring Creek Cemetery. In 2002 at a special ceremony attended by family, journalists and officials, a tombstone was erected that reads: “We chose freedom for mankind. On September 5th, 1945, in Ottawa, Canada, Igor, Svetlana and their young son Andrei escaped from the Soviet Embassy and tyranny.”

You can hear more stories about the people and events that helped shape Mississauga via our podcast, We Built This City: Tales of Mississauga, available on your favourite podcast platform or from our website.

I am really interested in knowing your sources for this story and learning more about Anna, Igor and family.

Its a great, true, but little-known story! The cold war really did originate in Canada! Both movies can be viewed in their entirety on YouTube. Rest in peace, Igor and Svetlana. You were true heroes!