The next time you’re taking off from Pearson International Airport look down at the small houses that hug the northern boundary because this is where one of Canada’s biggest national projects began.

Picture this: it’s 1942 and the Second World War is raging in Europe, Africa and the Pacific.

Thousands of Canadians are overseas, fighting in the conflict on land, at sea and in the air but victory is far from certain. France had fallen in June 1940 and Londoners were living with the reality of regular nighttime bombings.

The exhausted Allied countries needed more support – and the small farming community of Malton stepped up to deliver.

Malton, located in the northeast part of Toronto Township (later Mississauga) was already in the midst of change. In the late 1930s the Toronto Harbour Commission had purchased 13 local farms to create ‘a million-dollar, world class airport’ with the former Chapman farmhouse converted into the first airport terminal.

The Malton Airport officially opened on August 29, 1939, just days before the outbreak of the Second World War. It immediately became a base for the Royal Canadian Air Force, providing training for air crews from Canada and Great Britain.

Land was also set aside for National Steel Car’s factory, which began to build bombers. The plant needed a lot of workers, however there was no place for them to live. Malton wasn’t the only community with this problem. Canada’s wartime manufacturing and training surge had caused a nation-wide housing shortage.

Enter the Canadian government, which in 1941 used the War Measures Act to create Wartime Housing Limited, a Crown agency. It was led by Hamilton construction giant Joseph Pigott, the man behind the building of the Royal Ontario Museum, Hamilton’s McMaster University, the Bank of Canada in Ottawa, the Crown Life Insurance Company building in Toronto – and wartime housing in Malton.

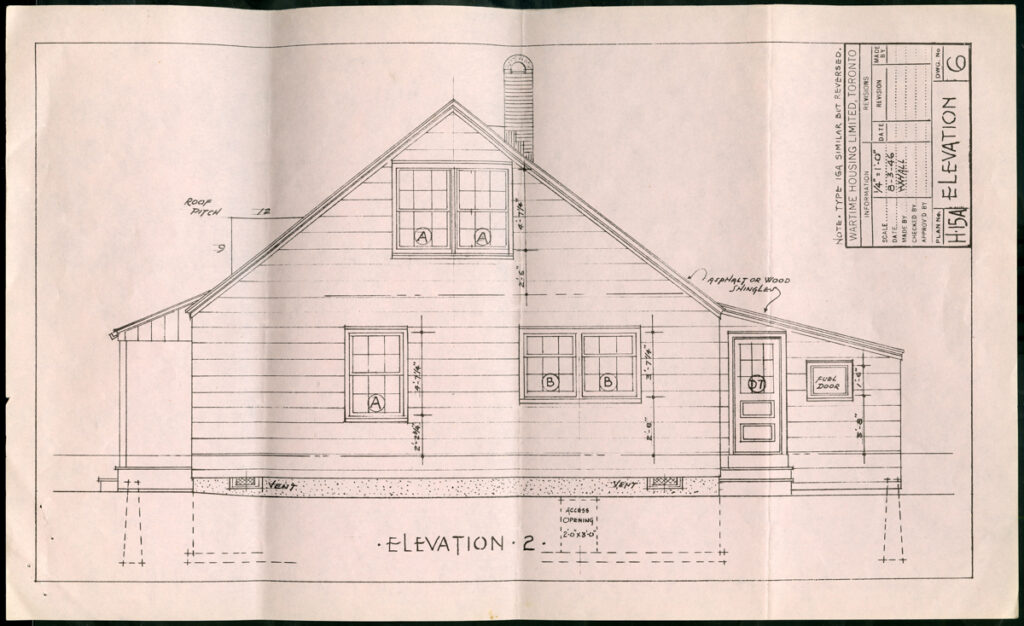

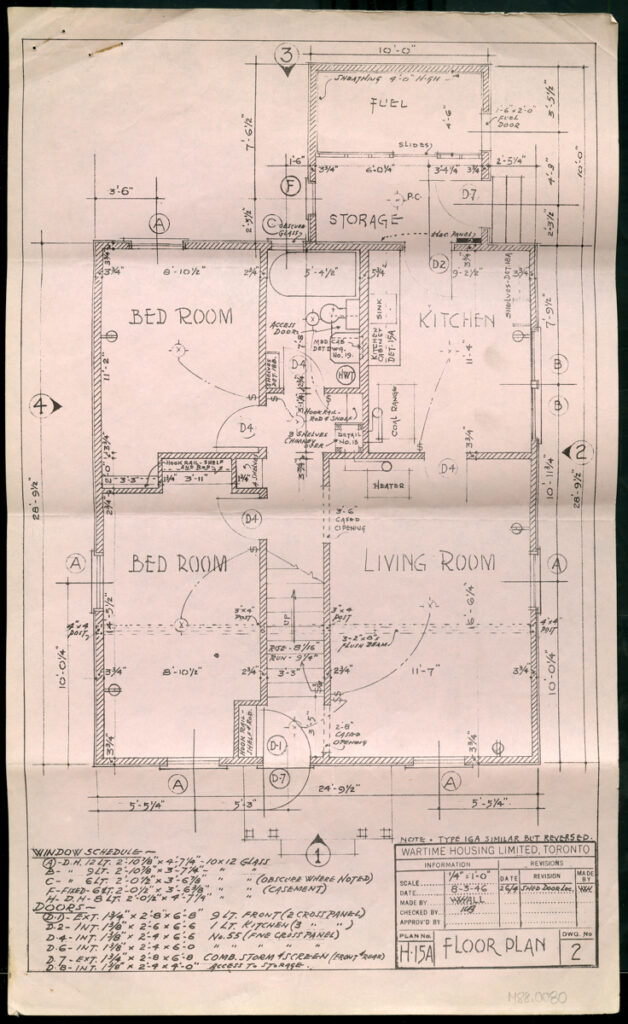

Architects quickly designed small homes for workers and their families, which they named Victory Houses, and the federal government contracted builders across the country to construct the homes near training and manufacturing sites.

In Malton, the government expropriated the Codlin farm in 1942 to create Victory Village, a subdivision of 200 homes.

The blueprints were for single storey or storey-and-a-half houses between 600 and 1,200 square feet that could be built quickly and efficiently with prefabricated materials and clapboard siding exteriors. In addition to the houses, surveyors designed and laid out streets, a community hall and a park – all of it near the airport to make it easy for workers to travel back and forth.

The construction sites worked like assembly lines to accelerate the build.

By 1942 Victory Village was welcoming families, just in time for a new boost in manufacturing output. That year the Federal government expropriated National Steel Car, renamed it Victory Aircraft and became a major producer of the Avro Lancaster bomber – the most famous of the Allies’ night bombers

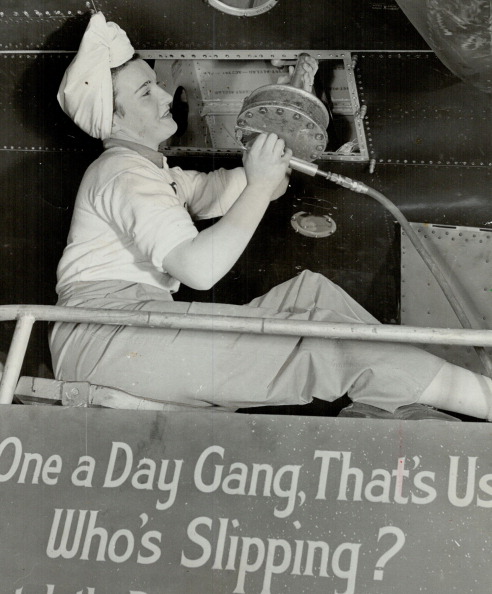

The Malton plant built 430 ‘Lancs’ between 1942 and 1945, and most of the assembly line workers were women, who worked as welders, riveters and testers.

In the evenings, workers, locals and servicemen training at the airport would gather at the Victory Community Hall for dances, many of them fundraisers for the war effort.

Today the neighbourhood, located at the northern corner of Pearson International Airport, remembers its past glory in the remaining small wartime homes that sit on Victory Crescent, Churchill Avenue and Lancaster Avenue, and in Victory Park where past generations of workers looked skyward to see what they could build.

Wonderful story Patricia, rich with information. I didn’t know that the Codlin farm was used for the housing.

My family lived on McNaughton Avenue, my aunt and uncle on Victory Crescent and my maternal grandparents on Merritt Street. My dad worked at Avro.

My family lived on Churchill Avenue. Relatives also lived in various places in Malton. My dad worked at Victory Aircraft, then Avro then DeHavilland Aircraft. My mom worked for the post office, delivering mail to rural areas where the airport is located now. Wonderful place to grow up.

Very interesting, I enjoy reading about Malton. Our family lived on Merritt ave. From 1968 until 1982.

I have learned so much about Malton and its history while researching information on Winston Hall and the Staff House for the book I’m writing about the history of Winston Hall.

I have uncovered five Winston Halls that existed! While my book will focus mainly on the one in Fort William (later Thunder Bay), I am including information about all of them!

Interestingly, all the staff houses (including the Winston Halls) were built for wartime workers at nearby factories and plants. Also, there are many similarities between the Winston Hall in Malton and the Winston Hall in Fort William, including the fact that both had bowling alleys and snack bars in their basements!

My family had a huge connection to the one in Thunder Bay. I grew up across the street from Winston Hall. One set of grandparents lived there, and my other pair of grandparents lived next door to me. My first apartment was in Winston Hall. My mom was the last person to own and run the store in the basement. Winston Hall meant—and still means—a lot to me. It also meant a lot to the thousands of people who lived there. That is one of the reasons why I’m writing about it. It’s a part of our history, and I want to document it, because it no longer exists, except in our memories, and I want to bring those memories to life again.